Note: this is a re-post of a blog post originally published in January 2017

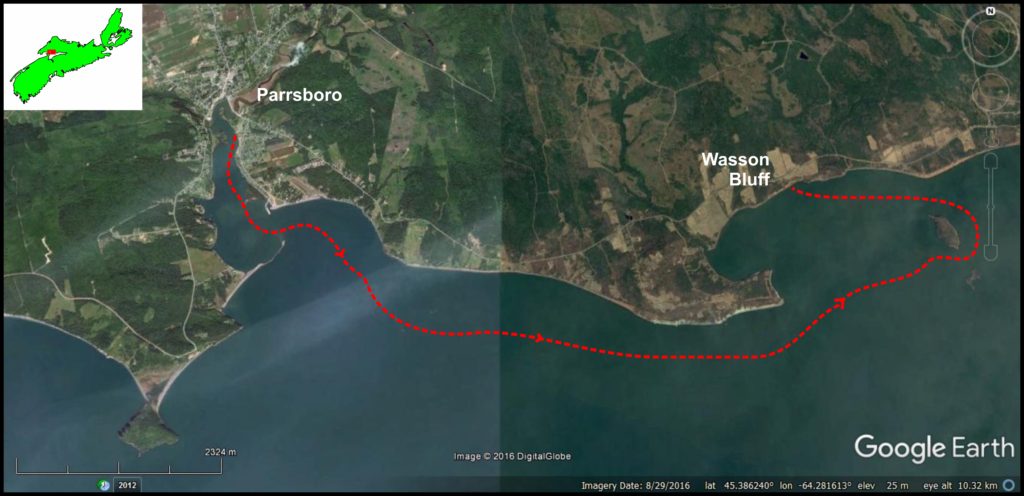

After my first visit to Five Islands and Parrsboro in early July of 2016 and having recently submitted my PhD thesis in Geology I was very keen to volunteer for a fossil dig or some kind of outreach activity with the Fundy Geological Museum. Luckily I was able to get in touch with Tim Fedak, The Director and Curator of the Fundy Geological Museum, who invited me to come along with himself and the Fossil Lab Manager Curator Regan Maloney for a fossil dig at Wasson Bluff on the shore of Nova Scotia’s Minas Basin. I was also told that I would be part of a pilot study for an integrated tourism experience involving travelling from the Fundy Geological Museum in Parrsboro to the Wasson Bluff fossil cliffs during high tide, by boat.

After meeting Tim and Regan early on the morning of July 29th at the museum we went to wait along the shore of Parrsboro Harbour for our ride. Soon, the faint sounds of an outboard motor are followed by the arrival of a 20 foot (or so) Zodiac boat, operated by Captain Randy Corcoran. Randy took us out of the harbour and into the Minas Basin, where on the way to Wasson Bluff we were treated to spectacular views of the coastline and geology of Clark Head. Next, we traveled east, toward and then around “Two Islands” (these are literally two islands). It is worth noting that while we were boating around Two Islands were about 1 – 1.5 km from shoreline. However, just over 6 hours later, during low tide, you could have walked to them from shore – meaning that twice a day, they aren’t even islands at all. By the way, the Minas Basin has the highest tides recorded ever in the world.

The geology and paleontology of Wasson Bluff

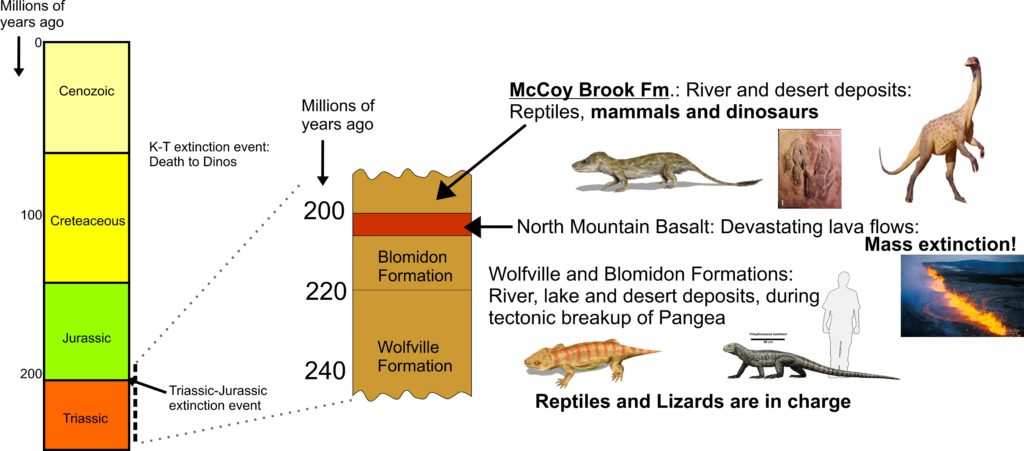

Wasson Bluff is a very significant, world-class fossil locality and contains the oldest fossil remains of dinosaurs in Canada. But it’s not only dinosaurs – there are important reptile and early mammal fossil finds at this location that have shed light on ecosystems that existed just over 200 million years ago following one of Earth’s “Big 5” mass extinctions: the Triassic-Jurassic boundary mass extinction event.

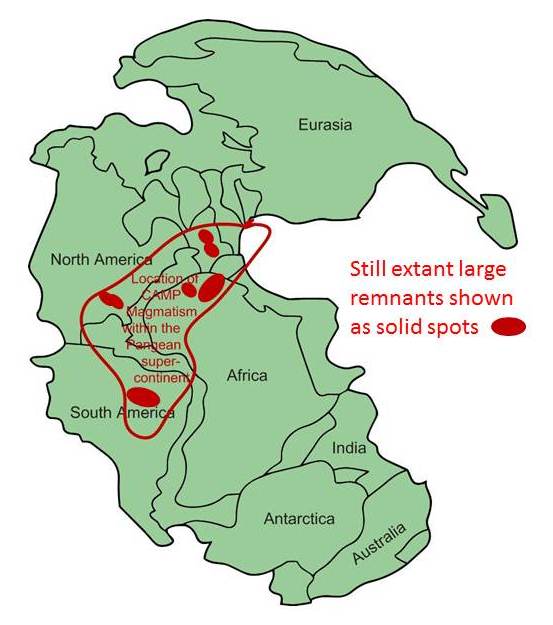

The Triassic-Jurassic boundary mass extinction event resulted in the extinction of about half of the worlds species over a period of 10,000 years, including the extinction of species from terrestrial habitats that would later be filled by the dinosaurs and mammals. Arguably it is as significant and devastating as the K-T extinction event, about 66 million years ago, that killed off all of the world’s large species, including all non-avian dinosaurs. The cause of Triassic-Jurassic boundary extinction is debated, but the most likely cause was the massive volcanic eruptions of the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province, or CAMP as it is also called. CAMP eruptions occurred as the supercontinent Pangea was being torn apart by tectonic forces, causing basaltic lava to pour out from the Earth’s mantle and spill over large parts of North America, South America, Europe and Africa. These massive eruptions also spewed out carbon dioxide, sulphur dioxide and aerosols, resulting in profound climate change that was just too much to handle for many unfortunate creatures in Earth at the time.

Today, a record of the devastating flood basalts of the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province are exposed on the northern shore of western Nova Scotia as the North Mountain Basalt, a prominent rock unit which forms the backbone of western Nova Scotia, as well as most of the coastline of Nova Scotia along the Bay of Fundy and the northern boundary of the scenic and mainly agricultural Annapolis Valley. I spent much of my youth hiking, camping and even partying along the shore of the Bay of Fundy, and the North Mountain Basalt has always fascinated me. It has many [perhaps subjectively] beautiful and interesting features, including amygdules and vugs filled by silicate minerals like the various zeolite minerals and even rare pink to dark purple amethyst, flow selvedges, columnar joints and distinct reddish paleosols (ancient soil horizons on the top of individual flows). In any case, the [perhaps subjective] beauty and interesting geology of the North Mountain Basalt belies the massive destructive power it yielded over life on Earth just over 200 million years ago.

The rocks at Wasson Bluff, belonging to the Early Jurassic McCoy Brook Formation, overlie the North Mountain Basalt, and therefore provide a record of the environmental conditions after the eruption of the North Mountain Basalt lavas. Therefore, the fossils at Wasson Bluff provide a record of the recovery and diversification of life following the extinction event. These rocks of the McCoy Brook are made up of lithified sand and mud, deposited in lakes and by dryland Rivers and deserts in the Early Jurassic about 200 million years ago. Deposition of these sediments occurred in a tectonically-active rift basin, somewhat like the modern East African Rift, that formed due to the tearing apart of parts of the Earth’s crust as North America was slowly becoming severed from Africa, leading to the opening of the Atlantic Ocean in the Early Jurassic, about 190 million years ago.

A number of significant fossils discoveries have been made in the McCoy Brook Formation at Wasson Bluff. Most notable are the many fragmentary specimens of small early mammal-like creatures called cynodonts of the genus Pachygenelus and Oligokyphus, abundant remains and possible trackways of the small crocodilian Protosuchus, and remains, including some near-complete skeletal remains of Clevosaurus, a small iguana-like reptile (but, not closely related to iguanas). However, what Wasson Bluff, and by association Parrsboro, is most famous and celebrated for are its dinosaur fossils. Notably, these include abundant remains and trackways of Prosauropods (similar to Massospondylus) – medium-sized, herbivorous or omnivorous, bipedal and/or quadrupedal dinosaurs, which were perhaps up to 3-4 m in length and weighing around 70 kg (150 lbs). These Prosauropods are related to the Sauropods – the largest dinosaurs and largest land animals ever to have inhabited the Earth. Other dinosaur fossils found at Wasson Bluff include the sparse remains of chicken-sized and very chicken-like Ornithischians, possibly Lesothosaurus.

Digging for bones

Once we were dropped off at the beach we unloaded a bit of gear and got to the task of digging for fossils. Regan and Tim were very patient with me and very accommodating, and I did my best to help. But, excavating was difficult work; the sun was hot, the rain fell now and then, and the actual act of excavation fossils required a lot of skill and dexterity. The fossil bones themselves are tiny – typically less than 1 or 2 cm long and only a few mm thick. To dig them out you really just have to dig the sand and clay out around them – BUT you have to be very careful. Several times early in the first day I accidently remove too much around the fossils or just poked the fossils themselves and – boink – there they go, lost on the beach for another 200 million years (NOTE: The Museum usually starts all new volunteers on small fragments that are less likely to be significant. :). But, by the end of the first day, I had successfully got the hang of things and had excavated a small tibia (?) from some kind of Protosuchid, Lepidosauror mammal-like cynodont. Most of what I excavated, however, was pieces or fragments of the scales and spines of the crocodilian Protosuchids.

I should also point out here that anyone who is interested in excavating fossils or doing fossil research in Nova Scotia needs a Heritage Research Permit (see https://cch.novascotia.ca/exploring-our-past/special-places for more details). Also, please keep in mind that natural history belongs to all of us, and if you do make a find it is best to report it to the Fundy Geological Museum or experts at nearby universities or at the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources.

One definite highlight of the first day was making it onto the 6 o’clock CBC news. Heading there I didn’t have a clue that we would end up being in the news, and so it was a surprise to me that this would happen. So, just after lunch Tim headed out to meet the CBC reporter and her cameraman/director. Once they showed up they interviewed Tim and the cameraman started taking shots of us doing “work”. My cameo was a 3 second shot of me using a small hand-held brush to “clean” the surface of the rock… or something. Actually I don’t really know what I was supposed to have been doing, but the camera dude loved it and seemed genuinely fascinated by my technique.

At the end of the day there wasn’t going to be a boat to pick us up. In fact, it wasn’t even an option since the tides had moved the shoreline out hundreds of meters and maybe a kilometer out into the Minas Basin. So we had to walk out and catch a ride.

Fundy Geological Museum and The aspiring Fundy Cliffs Geopark

The part of the Nova Scotia shoreline along the northern side of the Minas Basin from Economy to Cape Chignecto and the adjoining coastline along the southern side of the Cumberland Basin have a long history of geological and paleontological discovery, and contain sites of Global geological and paleontological significance. The most notable site in this area is the Joggins fossil cliffs, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site known for its incredible and important Carboniferous fossil assemblage, and for the degree of fossil preservation, including the preservation of tress standing straight up. In fact, knowledge of the renowned fossils at Joggins once reached none other than Charles Darwin, who actually mentions the Joggins fossils cliffs in On the Origin of Species.

But, that is Joggins, and Joggins consists of a succession of rocks that were deposited ~100 – 120 million years before the sandstones and mudstones at Wasson Bluff. Also, the fossils at Joggins were discovered and studied much earlier, from the 1820’s onward. By comparison, the fossil finds at Wasson Bluff are relatively new, with the initial discovery of the postcranial remains of a sauropodomorph dinosaur by Paul Olsen of Columbia University in 1976, while working with the eminent paleontologist Donald Baird of Princeton University. Later, small dinosaur footprints were discovered by veteran gem and fossil hunter, amateur geologist and Parrsboro native Eldon George in 1984. This sparked renewed interest in the site, and as a result a group of American paleontologists led by Paul Olsen undertook an excavation in 1896, recovering hundreds of thousands of bones. Then, in 1993 the Fundy Geological Museum was established in Parrsboro, where many of the finds from Wasson Bluff are curated and put on display. Now, there is a movement, led by community members in Parrsboro and geologists in Nova Scotia and across Canada to establish a geopark on the Parrsboro shore – called the aspiring Fundy Cliffs Geopark.

Sieving for Bones

After the first day I went to camp overnight at the Five Islands Provincial Park, a place where the same rocks as those at Wasson Bluff are spectacularly exposed. However, unlike at Wasson Bluff, the rocks of the McCoy Brook Formation exposed at Five Islands aren’t known to contain many fossils. Nevertheless, leave it to an Ontario geologist – Derek Armstrong of the Ontario Geological Survey – to find a spectacular specimen of the footprint of a small, bipedal dinosaur called Anchisauripus right on the Beach at Five Islands while on vacation (http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/dinosaur-footprint-fossil-nova-scotia-anchisauripus-1.3797031). Unfortunately for me I was not so lucky – Or maybe I just walked right over them without noticing, I dunno.

Anyway, the next day I returned to Wasson Bluff with Regan, Tim and a new friend Laura Broom, now an MSc student at Dalhousie University. During the second day I was put to the sieve. Tim and I would collect samples from a few layers, I would break them up (the rocks were very soft – “poorly lithified” as we geologists would say) put them in bags with water and let them slowly break down. Then, after letting the rocks transition into a soupy mess of mud, sand and water, I placed the mixture into a sieve and rinsed it over and over again until I could see small bones and fragments. Then, with tweezers I picked the bones out and placed them in small sample bags. Apparently I made some interesting finds, including numerous limb fragments, body armour scutes, a few small teeth, but also a rare and important find of a complex bone that may come from the jaw joint of a the mammal-like reptiles. The Museum continues to examine the specimens as part of ongoing research project.

Later that day we had visitors – about 30 of them. Tim and the other employees at the Fundy Geological Museum had advertised and arranged a public site visit to Wasson Bluff, and it was really great to see such interest from visitors and even some locals.

Visit Parrsboro and the Fundy Geological Museum! Despite growing up in Nova Scotia and doing my bachelor’s degree at Acadia University, the summer of 2016 was my first time visiting to Parrsboro or the Fundy Geological Museum. I really regret that, as now I see what I have been missing. Not only does this area have amazing scenery, but its geological heritage and significance is truly world-class. Summer time is the best time to go, and next summer there will be a lot happening with the museum and at Wasson Bluff, including the brand-new Fundy Dinosaur Dig and Boat Tour (http://fundygeological.novascotia.ca/fundy-dinosaur-dig-boat-tour). Having done this myself I can say it is a one of a kind experience. You too can find (or break and lose) scientifically important specimens of reptiles, early mammal-like animals and (if you are lucky) dinosaurs! Not only do you get a rare chance to experience the scenery of the Minas Basin from the basin itself, but you also get the opportunity to experience world-class paleontology of Wasson Bluff under the capable guidance of Tim Fedak and his colleagues at the Museum. Also, there are guided tours to Wasson Bluff occurring throughout the summer (http://fundygeological.novascotia.ca/events). But, you don’t have to wait for summer time to come; the museum is open year-round and always has exhibits and knowledgeable staff on hand. They also regularly host public lectures. For more information, see the Fundy Geological Museum website: http://fundygeological.novascotia.ca/ or check them out and follow them on Facebook.